5. Remediation Methods

Many factors must be considered when selecting one or more methods for remediating PCBs in indoor air or removing PCB-contaminated materials during renovation or demolition. Among other things, the choice will depend on contamination type, remediation target, and the expected lifespan of the building.

This section explains the principles behind remediation methods, including removal of PCB-contaminated materials. Methods for physical removal apply to renovation and demolition as well as remediation of excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air. Interventions to mitigate excessive PCB content in indoor air will often comprise a combination of remediation methods (Haven & Langeland, 2016).

Physical removal of PCB-contaminated materials generates waste and is thus subject to the Statutory Order on Waste (Ministry of the Environment, 2012) and the Statutory Order on the Landfill of Waste (Danish EPA, 2013) (see Section 7.1, Regulations). The descriptions of the various remediation methods provide answers to the following questions:

- How does each method work?

- Which source types do the methods apply to?

- Is there any case-study information on the implementation of the methods?

- What health and safety concerns should be considered?

- How do the applications of the methods affect building usage?

- How durable are the methods?

- How expensive are the methods?

Finally, the practical aspects of applying the methods will be discussed. Pros and cons of the methods are listed in table 12, Section 5.11, Remediation Methods – Pros and Cons.

Annexes A and B detail experiments with bake-out and extraction as remediation methods. Annex C describes the mitigation of excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air in the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate where physical removal of PCB-contaminated materials was conducted, in combination with bake-out and encapsulation.

5.1 Physical Removal

Physical removal means the removal of PCB-contaminated materials from the building. This may reduce excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air, but physical removal is also used when separating out PCBs from PCB-contaminated waste (in keeping with the Statutory Order on Waste (Ministry of the Environment, 2012) and to the Statutory Order on the Landfill of Waste (Ministry of the Environment, 2013) (see Section 7, Waste Management).

5.1.1 Remediating PCB in Indoor Air – Mode of Action

Physical removal of the contamination source results in a permanent reduction in emissions and potentially a permanent reduction of PCB concentrations in indoor air. The effect of source removal will depend on how residual sources are treated.

It may be time-consuming to achieve satisfactory PCB concentrations in indoor air as any handling of PCB-contaminated materials can lead to the dispersal of PCB-contaminated dust and increased off-gassing from exposed surface areas, which may in turn contaminate other materials (e.g., Haven & Langeland, 2011; Sundahl et al., 2001; Kuusisto et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2011). For reasons of health and safety, to protect the surrounding environment, and to avoid recontamination of other materials, it is vital that any dispersal of PCB-contaminated materials and dust is avoided during the work.

5.1.2 Removable Source Types

In principle, it is possible to remove all source types (i.e., all types of PCB-contaminated materials regardless of origin) but in practice there may be structural issues rendering this impossible or the clean-up techniques may be prohibitively expensive.

Remediation

When abating unacceptable PCB exposure levels in indoor air, caulk containing PCBs, porous materials such as concrete and clay tiles, paint, and ceiling panels will often be removed. It is also possible to remove insulated glazing units with PCB-contaminated edge sealant and PCB-contaminated fixture materials, or capacitors containing PCBs.

Figure 5. PCB-containing caulk is a primary source and can be removed by cutting it out (see Section 5.1.11, Caulk and Adjacent Building Materials).

In theory, all caulks can be removed, but removing the adjacent materials subject to secondary contamination may pose a problem. In these cases, the load-bearing capacity and top layer of individual structures should be assessed, and the location of power installations must be identified, etc.

Figure 6. Concrete adjacent to the PCB-containing caulk is a secondary source and can be removed by cutting out the concrete (see Section 5.1.11, Caulk and Adjacent Building Materials).

To remove surface-area contamination in tertiary sources, first ascertain whether the surface will tolerate the technique (e.g., sandblasting). It may be advisable to remove tertiary contaminated surface areas, especially those prone to PCB absorption. These could be insulation or sealants made of polyurethane foam, back stops, or foam in upholstery, and certain floor finishes.

Figure 7. Blasting with sand or metal shot or with a mix of metal and foam rubber on surface areas can remove PCB-contaminated material to a depth of approx. 5 mm (see Section 5.1.12, Surface Coatings).

Renovation and Demolition

According to the Statutory Order on Waste, PCB-contaminated materials removed from the building must be sorted and classified and PCBs must be separated out from materials for recovery.Waste-generating enterprises must sort the part of their industrial waste that is suitable for recovery (see Section 7.3, Sorting Construction and Demolition Waste with PCBs).

All PCB-contaminated material can, in theory, be separated out. However, in practice, there may be structural issues which render it impossible or very expensive. It may be very resource-intensive and complicated to separate PCB-contaminated paint from the actual building materials, for example. This is true whether the PCB-contaminated paint is a primary, secondary, or tertiary source.

An assessment must be made in consultation with the local authority as to which materials to separate PCBs out from and which removal or clean-up techniques to use (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 3 Surveys prior to renovation or demolition (Andersen, 2015)). The choices might depend on issues relative to health and safety, protecting the surrounding environment, and the presence of other environmentally harmful substances.

5.1.3 Practical Experience with Physical Removal

Experience from Germany indicates that lasting success of remediating excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air requires total removal of the primary sources. If possible, secondary sources occupying large surface areas should also be removed. If not, their PCB emissions to the indoor air may be reduced by encapsulating them (Bonner, 2011). In German terminology, secondary sources cover what, in this book, is defined as secondary and tertiary sources (see Section 1.1, Spreading of PCBs and SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 1.5 Primary, secondary, and tertiary sources (Andersen, 2015)).

In the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate, PCB-containing caulk was abated in several blocks of flats. Several primary, secondary, and tertiary sources were physically removed. Subsequently, further remediation involving encapsulation and bake-out was carried out. The interventions achieved very positive results. The renovation reduced indoor-air PCB concentrations in vacated flats with lowered temperatures from levels of 700–1,500 ng/m3 to below 300 ng/m3 (Lundsgaard, 2013) (see Figure C1 in Annex C). PCB remediation of the Farum Midtpunkt flats presents an overview of air concentrations and remediation results in these flats.

Positive outcomes were reported following the renovation of a school in Germany where PCB-containing caulk and paint were removed. Manual removal of caulk, ceiling panels, PCB-contaminated radiator paint (primary sources) was carried out along with high-pressured water cleaning of walls, etc. These measures reduced the total PCB concentrations in indoor air from approx. 6,000–7,000 ng/m3 to below 600 ng/m3 (Bent et al., 2000). An additional German case indicates a marked reduction of PCB concentrations in indoor air by removing wall paint using a caustic substance (Bent et al., 1994).

5.1.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

All handling of materials containing PCBs requires health and safety measures, precautions preventing emission to the outside environment, and waste separation.

Steps must be taken to ensure that the building structures can tolerate the removal of certain materials.

Removal may be implemented with or without the use of power tools. Manual methods may be preferable because they typically generate less dust, off-gassing, and residual waste. This makes it easier to avoid spreading PCBs. Moreover, manual methods generate less noise and vibration.

Sandblasting concrete walls is a very dusty process requiring many precautionary measures relative to health and safety and emissions to the outside environment.

Removing PCBs as part of remediation will remove health risks. However, it is almost impossible to remove all PCBs and the resulting PCB concentrations in indoor air will depend on the management of the residual sources.

5.1.5 Using the Building

The affected areas must be vacated and screened off and access prohibited for unauthorised persons. PCB spreading from the work area must be prevented. Other building occupants may be inconvenienced by noise from power tools.

5.1.6 Time Frame and Remediation Resilience

The complete removal of PCB-contaminated materials is hardly possible and physical removal will often be combined with other remediation methods. This means that managing the remediation process and handling the residual sources are crucial for long-term results.

5.1.7 Costs

There are costs associated with the actual work and with health and safety issues, waste, and clean-up. Removing PCB by sandblasting or blasting using other materials is costly and these methods must therefore be viewed in relation to contamination levels and other potential contaminants such as lead. Section 2.3.5, Experience-based price estimates details experience-based prices for specific work processes.

5.1.8 Physical Removal in Practice

These Guidelines refer to several other guidelines and reports concerning the removal of PCB-contaminated materials:

- Branchevejledning om håndtering og fjernelse af PCB-holdige bygningsmaterialer (Trade Guidelines for the Management and Removal of PCB-

- Contaminated CDW) (BrancheArbejdsmiljøRådet for Bygge og Anlæg, 2010)

- Vejledning og beskrivelse for udførelse af PCB-renovering (Guidelines and Specifications for Implementing PCB Renovation) (Dansk Asbestforening, 2010)

- PCB-vejledning (mini-udgaven) (PCB guidelines (short version)) (Copenhagen City Council, 2014)

- Rapporten Åtgärder vid renovering av PCB-haltiga fogmassor (Measures Associated with the Renovation of PCB-Containing Caulk) (Rex & Sikander, 2006).

The report Metoder til fjernelse af miljøproblematiske stoffer (Methods for Removing Environmentally Harmful Substances) reviews methods for removing several environmentally harmful substances in connection with demolition or renovation (Olsen & Olesen, 2015). It outlines applicable technologies for identifying and removing environmentally harmful substances and is based on a literature survey and collection of data on practices and experience from the trade.

Choice of methods for removing PCBs is dependent of the prerequisites in each separate case. Prior to physically removing building materials, the following practical considerations should be made:

- Which PCB-contaminated materials can be removed?

- Which tools can be used?

- How should adjacent materials be treated?

- How should surface coatings be treated?

- How should other materials such as insulated glazing units be treated?

These issues are discussed in the following sections.

5.1.9 Which Materials Can Be Removed?

When PCBs have been confirmed in materials to be removed from a building via remediation, renovation, or demolition, Copenhagen City Council requires, as a minimum, that PCBs deposited on hard surfaces (e.g., concrete) are cleaned off while wood is not subject to clean-up (Copenhagen City Council, 2014). Any PCB-contaminated paint on concrete walls must thus be removed. In the case of PCB-contaminated floor varnish on a wooden floor, the floor plus varnish is sent to an incineration plant with permission to incinerate waste of the given classification.

When PCB-contaminated materials are removed from a building which is not destined for demolition, the solution achieved is permanent and this will often comprise removal of caulk, porous materials (concrete, clay products), paint, and ceiling panels.

Insulating glazing units whose edge sealant contains, or is suspected of containing, PCBs or are mounted using materials containing PCBs should be removed. Capacitors containing PCBs should also be removed. Handling PCB-contaminated building materials indoors should be done with the utmost care, as there will otherwise be a risk of spreading the PCBs and of contaminating the building again. All loose furnishings such as curtains, blinds, and carpets should be removed to facilitate the subsequent clean-up and to avoid any further contamination.

PCB spreading may occur via dust, residual materials, waste, etc. Caulk residues dropped on the floor and trodden underfoot may cause off-gassing to the indoor air for several years to come. PCB in indoor air can be deposited on surface areas resulting in their contamination. Even minute quantities may cause issues. 1 g of PCB will take 44 years to off-gas in a room measuring 17 m3 with an air exchange rate of 0.5 h-1 and the lowest PCB exposure level action value in the indoor air of 300 ng/m3 (see Section 5.6, Ventilation). Section 6.3, Spreading of PCBs to the Surrounding Environment outlines how to avoid the spread of PCBs.

Handling PCB-contaminated materials may lead to elevated PCB concentrations in indoor air (e.g., due to exposed surface areas). In cavities, PCB levels may be high because the rate of air exchange is very low. If this cavity is opened during work, attempts should be made to increase the air exchange rate in the cavity facing the outside before opening it from the inside.

5.1.10 Tools

All PCB-related guidelines include the question of whether to use power tools. Methods not applying power tools are best suited to primary sources such as caulked joints not chemically bound to the adjacent materials. If power tools are used, steps must be taken to safeguard health and safety in terms of screening dust and gasses, as well as noise and vibrations. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the following when using power tools:

- It becomes harder to avoid dispersal of dust and residual waste

- The objects being cut or drilled will, to some extent, be exposed to heating

- Noise and vibrations may inconvenience building occupants.

In a Swedish survey, external caulk and a few millimetres of the adjacent concrete were removed by means of mechanical tools connected to a high-capacity vacuum cleaner. The survey indicated that even minor faults such as the vacuum cleaner hose coming off could result in high PCB concentrations in the air (Sundahl et al., 2001).

Power tools will, to a certain extent, heat the objects being cut. This may cause increased PCB off-gassing. However, a Swedish survey has indicated that the temperature will rise to max. 70 °C when cutting out caulk from concrete using various power tools (cutting using an angle grinder and grinding using an angle grinder and an abrasive pencil, respectively) (Rex & Sikander, 2006).

According to Annex A in the At-intern instruks IN-9-3, PCB i bygninger (Internal WEA brief IN-9-3, building-related PCB) (Danish WEA, 2014), wet tile cutters should not ordinarily be used for materials containing PCBs as PCB-contaminated water can be difficult to collect.

5.1.11 Caulk and Adjacent Building Materials

Caulk

Physical removal of caulk can be done by cutting it out. This can be done manually or by using power tools. BrancheArbejdsmiljøRådet for Bygge og Anlæg has published detailed guidelines on how to prepare the work area and which work methods to use when removing external and internal caulk (BrancheArbejdsmiljøRådet for Bygge og Anlæg, 2010). Guidelines from Dansk Asbestforening (Danish Asbestos Association) also offer advice (Dansk Asbestforening, 2010), excluding simple work lasting less than a day (Dansk Asbestforening, 2016). The guidelines also discuss what to do if adjacent materials need to be removed. Figure 8 shows how to remove caulk using power tools and suction.

Figure 8. Removal of caulk using power tools and suction. Photo: Tscherning A/S.

Adjacent Materials

PCB from caulk can be transferred to adjoining materials. Mapping results from the building will disclose the extent of contamination in the adjacent materials (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs,2.5 Mapping of building materials (Andersen, 2015) and SBi-anvisning 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCB, 8.7 Secondary contaminated material (Andersen, 2015)).

Experiments were conducted on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate to discover the method best suited to remove caulk and adjacent contaminated concrete (Lundsgaard, 2010). The contamination of the concrete indicated that PCB levels were reduced to below 50 mg/kg just under 30 mm away from the joint. Experiments have been made with cutting out caulk from joints and grinding down concrete and this procedure proved to leave behind contaminated concrete surfaces with higher off-gassing rates of PCB than the intact joints. Experiments were also conducted where caulk was removed around doors by making a cut through the wall approx. 50 mm away from the joints and removing caulk and concrete along the door opening. This method reduced the off-gassing significantly compared to cutting out the caulk and grinding down the adjacent concrete.

Consideration must be given, in each individual case, as to what should be done about secondary sources and whether it is possible to cut out all or part of the contaminated material.

In demolition projects, it will usually be necessary to separate the adjacent contaminated material from the rest, for reasons of correct waste handling.

Secondary contaminated material can, for example, be removed by cutting it out with or without using power tools (see guidelines from BrancheArbejdsmiljøRådet for Bygge og Anlæg (BrancheArbejdsmiljøRådet for Bygge og Anlæg, 2010) and Section 6, Protecting People and the Environment).

It is possible to examine the depth to which the secondary contamination has penetrated the concrete by mapping and collecting samples (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 5 Mapping of building materials (Andersen, 2015) and SBi-anvisning 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 8.7 Secondary Contaminated Material (Andersen, 2015)).

It would be best to cut at a spot where the concrete is not contaminated, but practical considerations such as load-bearing capacity, reinforcement, installations, or the location of the source may render it impossible to cut at the preferred distance to the joint. If contaminated material is cut, adequate steps must be taken to minimise the generation of PCB-contaminated dust and gas. Figure 9 shows the removal of concrete adjacent to a door joint with reinforced concrete above the door.

If the structure allows the secondary contaminated material to be cut out around door or window openings, a larger-sized door or window could subsequently be fitted, or the seam be remade in new PCB-free materials before refitting the window or door.

Figure 9. Concrete adjacent to door joint has been removed.

In some cases, caulk and adjacent materials are cut out in a single process. Subsequently, the caulk could be separated from the adjacent material at a suitable site outside the building when precautionary measures are taken to safeguard against among other things dispersing contaminated materials (Rex & Sikander, 2006).

If the building is destined for demolition, contaminated adjacent materials which cannot readily be cut out can then be removed in tandem with the demolition. Cutting out material from supporting structures can be performed when they cease to be load bearing or structurally necessary. Complete elements may be removed and contaminated materials cut out at a suitable site away from the building.

Figure 10. When this school was demolished, certain PCB-contaminated materials were removed while storeys were demolished.Practical Experience with Specific Tools

A conical abrasive pencil can effectively grind down joints in the innermost corners and other places which are difficult to reach (Rex & Sikander, 2006).

In a Swedish survey, grinding using abrasive pencils has proved to emit less contaminant into the air than grinding using an angle grinder. Consequently, abrasive pencils are considered best suited to indoor renovations (Rex & Sikander, 2006).

5.1.12 Surface Coatings

Surface coatings such as paint, floor varnish, etc., can usually, but not always, be ground away. An assessment must be made as to whether the stability and durability of walls will be affected by such treatments. An assessment should also be made as to how much of the underlying material has been contaminated and hence how deep the removal process needs to reach.

Sandblasting Porous Surfaces

Typically, porous surfaces (such as concrete) containing PCBs are sandblasted when the contamination is limited to the outer 5 mm. During sandblasting, finely-grained abrasive sand is blown on to the surface to remove the top layer and some of the porous material underneath. This typically generates 20 kg of contaminated waste per m2, depending on the thickness of the surface layer being removed. Figure 11 shows a sandblasted concrete wall in a room where the floor finish has been removed.

Figure 11. Sandblasted concrete walls with the floor finish removed.Sandblasting concrete walls is a very dusty process requiring several precautionary measures to ensure the health of workers and occupants and to prevent emissions to the outside environment.

After sandblasting, the dust must be removed from the surfaces by cleaning. A Finnish survey indicated that, following sandblasting painted walls with a relatively small PCB content, effective vacuum-cleaning, and washing of the walls were necessary before surface PCB concentrations were low enough for dermal contact (Kuusisto et al., 2007).

Figure 12 shows protective clothing with fresh-air supply used during sandblasting concrete surfaces.

Figure 12. Person wearing protective clothing with fresh-air supply when sandblasting concrete surfaces.

The sand applied is mixed with stripped-off materials during the sandblasting process. When working in multi-storey residential buildings for example, careful planning is essential for safe removal of sand and stripped-off materials from higher elevations to a place of storage, until it can be sent to landfill or destruction. Furthermore, the weight load on the storey partitions must be considered during sandblasting and whether clean-up and removal should be carried out in stages to avoid excessive strain.

Shot-Blasting Porous Surfaces

It is possible to shot-blast the surface using metal shot of varying sizes. This can be more effective than sandblasting when part of the actual building material must be removed. Metal shot is reusable (Mitchell & Scadden, 2001). A ‘Steel Re-Jet’ method has been introduced on the Danish market for stripping PCB from floors and walls, shot-blasting the surface with small metal shot at high pressure to clean it. The character of the surface and the size of the metal shot determine the removal depth and how the surface structure will look afterwards.

This removal technique is dusty and requires precautionary measures for health and safety and protection of the outside environment. The system was developed so that simultaneous or subsequent vacuum-cleaning of the waste sends the mixture of stripped-off material and metal shot into a sealed separation system where the metal shot is separated from the PCB-contaminated residue. Metal shot can be reused while the quantity of waste comprising the stripped off material is automatically sealed in drums.

Shot- and Foam-Blasting Porous Surfaces

A method exists where a mix of metal shot and foam rubber is blasted on to the surface, namely the Sponge-Jet method (Maskinteknik, 2013). This method generates less waste and the blasting material can be reused. It is also applicable for gentle surface stripping.

Other surface-stripping techniques exist, but as yet there is little practical experience of their use in Denmark. One method is ‘CO2-blasting’ or dry-ice blasting where small pellets of frozen CO2 are blasted against the surface. This generates less waste than ordinary sandblasting. It is also possible to ’wash’ walls, ceilings, and other surfaces using high-pressure water-jetting. If the pressure is increased, water can remove porous material below the surface coating. The water is collected and disposed of according to applicable rules (Mitchell & Scadden, 2001). This method requires the surface to be moistened and water content, drying time, and subsequent treatment will be subject to assessment. Water content and drying time is described in the Byg-Erfa info sheet, Fugtkriterier og risikovurdering ved nybyggeri og renovering (Moisture Criteria and Risk Assessment for New Builds and Renovation) (Byg-Erfa, 2012).

In demolition projects, clean-up (of concrete slabs for example) can be done at a suitable site outside the building where the necessary precautionary measures can be taken to prevent the spreading of contaminated materials (e.g., Rex & Sikander, 2006)

Cleaning Non-Porous Surfaces

Paint can be removed mechanically or chemically from non-porous surfaces like metal. Mechanical removal could include sandblasting, ’CO2-blasting’, manual scraping, or grinding (Mitchell & Scadden, 2001). Here, too, it is possible to clean using shot-blasting such as the Steel Re-Jet or Sponge-Jet techniques mentioned above. Chemical removal can be performed using ordinary paint stripper, but the paint stripper will probably need to be mechanically removed afterwards.

Floor Finishes

It is relatively easy to remove linoleum or other floor finishes, but any residual flooring adhesives should be investigated to discover whether they contain PCB and thus need grinding off and, if so, which precautionary measures should be implemented.

5.1.13 Removal of Other Materials

Insulating Glazing Units

Insulating glazing units can be removed from the building and a decision made as to whether the actual window casing should be replaced due to potential contamination from edge sealants or fixture materials. If the window is surrounded by a caulk containing PCBs, it will usually be advisable to remove the entire window, including the casing, as this is likely to be contaminated.

It is relatively simple to remove insulating glazing units mounted with rubber sealant, weather strip, and top sealant, if applicable. Insulating glazing units mounted in putty or sealant tape in wooden casings can only be cut out using a special cutter. If the putty or ductile sealant tape has hardened, it might be necessary to smash the glazing to remove it.

It is not usually viable to reuse casings as PCBs may have migrated into the wood and there is a risk that the edge sealant of the new insulating glazing units would in turn become contaminated. In such cases, the complete window, including the glazing units, is removed and everything sent to a treatment plant. The Danish EPA has published guidelines on handling and removal of PCB-contaminated insulating glazing units (Danish EPA, 2014).

Capacitors

If there are fluorescent light ballasts with capacitors potentially containing PCB, it is advisable to remove the capacitors or ascertain that they do not contain PCBs (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 5.2.4 PCBs in capacitors (Andersen, 2015)). Capacitors containing PCBs must be handled carefully to avoid emissions and given to enterprises approved to handle PCB-contaminated waste. The Danish EPA has published guidelines on handling fluorescent light capacitors containing PCB (Danish EPA, 2015).

Furnishings and Insulation Materials

Furnishings can be tertiary contaminated sources of PCBs via sorption of airborne PCBs. This applies especially to chairs, sofas, and foam-rubber gymnastics mats, as foam rubber is particularly prone to sorb airborne PCB. It also applies to polyurethane foam used for insulation.5.2 Extraction

Extraction comprises reducing PCB content in contaminated materials, thereby modifying the source. Thus far, in Denmark, this method has been used where it is necessary to reduce excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air.

5.2 Extraction

Extraction comprises reducing PCB content in contaminated materials, thereby modifying the source. Thus far, in Denmark, this method has been used where it is necessary to reduce excessive PCB exposure levels in indoor air.

5.2.1 Mode of Action

Like other chemical substances, PCBs will diffuse towards areas with lower concentrations. It is possible, therefore, to remove PCBs from materials by applying a layer to the surface capable of absorbing PCBs. If PCBs have migrated from a PCB-contaminated joint into adjacent materials, the old joint can be replaced by a new PCB-free one, thus reversing the process and causing PCBs to migrate towards the new joint. This process is extremely slow and will take years.

The time span can be reduced by extracting PCBs from the building material. For example, a paste-like substance containing solvent is applied to the surface. The solvent penetrates the PCB-contaminated building material, dissolving the PCB, which will then migrate into the paste. The paste or extraction agent on the surface can be mixed with substances that will break down PCBs (see Section 5.3, Chemical Breakdown).

Figure 13. PCBs can be extracted from materials by applying a paste containing a solvent, for example. The agent penetrates the material and dissolves the PCB, which will then migrate back into the paste.

5.2.2 Types of Treatable Sources

This method can, in theory, be applied to all three source types, but in practice, the method is not applicable to primary sources with high PCB concentrations.

The extraction agent will only mobilise PCBs while they are moist, which means that they must be covered by foil to protect them from drying out (Krag & Kastberg, 2012).For this reason, the method tends to be best suited to secondary sources with limited surface areas. Typically, they are used where secondary sources cannot be physically removed for structural reasons.

5.2.3 Practical Experience

Certain Danish studies involving a few square metres of wall or floor have indicated that the method is likely to effectively remove PCBs from accessible surfaces in building materials. PCB extraction experiments have been conducted on surface areas of painted tertiary contaminated concrete and on secondary contaminated concrete door rabbets. These studies were conducted with an extraction agent known as NMTS (Non-Activated Metal Treatment System).

The extraction agent also exists in a version with a mixture of substances which degrade PCBs during extraction, the so-called ATMS method (Activated Metal Treatment System). This is a patented method where an agent is applied, mixed with metal components, which degrade PCBs (see Section 5.3, Chemical Degradation).

Various Danish laboratory trials have been conducted using different types of extraction agents. The results are described in Appendix B. Results from Extraction.

Laboratory trials indicate that the ATMS method is effective for relatively thin PCB-contaminated sources such as paints and primers while the method is less effective for thick materials such as concrete where the solvent will only penetrate the material to a limited extent (Liu et al., 2012). The thickness of the source and the penetration depth of the solvent can be used to assess how effective the treatment will be. The extraction efficiency was not dependent on the tested concentration levels (Liu et al., 2012).

In a field study conducted in the USA, good results were achieved for the extraction of PCBs in paint on industrial structures such as concrete buildings and metal surfaces (Saitta et al., 2015). The goal was to achieve a PCB concentration below 50 mg/kg on the given surface areas. PCB concentrations in paint were reduced by 95 % on concrete and 60–97 % on metal, respectively. The majority the extracted PCBs were removed within the first week.

The ATMS method and other extraction methods are rarely used in Denmark (Olsen & Olesen, 2015). The methods are not applied in those cases describing abatement interventions to mitigate elevated PCB exposure levels in indoor air collected by Haven & Langeland (Haven & Langeland, 2016).

5.2.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

Special health and safety rules apply in connection with handling the solvents used to mobilise PCBs. Additionally, the extraction agent used must be handled and disposed of in accordance with the rules applicable to PCB-contaminated waste.

The method does not generate dust, which is advantageous as it avoids the dispersal of PCB-contaminated dust.

Measures must be implemented to mitigate fire risk connected with chemicals used.

5.2.5 Building Usage

The off-gassing of the solvents to indoor air implies that no building occupants must be present in the room during the extraction process. It is often necessary to repeat the treatment of a given building material, which may take up to three months and building occupants will therefore have to move elsewhere.

5.2.6 Time Frame and Resilience

The long-term effect of the method is not yet documented. It is probable that the extraction agent will, to a large extent, remove the PCB contamination. In a study where a painted tertiary contaminated concrete surface area was treated, the extraction agent contained 50 mg of PCB per kg extraction agent after the first treatment (Krag & Rasmussen, 2011b). This corresponds to 150–300 mg of PCB being removed per m2.

A small quantity of PCB can volatilise and migrate further into concrete for example. The long-term effect of this is, as yet, unknown. This was observed at the first treatment of a painted door rabbet, but the concentrations subsequently dropped again (Krag & Rasmussen, 2011a). It was also observed during the treatment of a door rabbet where the caulk had been removed (Frederiksen et al., 2015) (see Appendix B. Results from Extraction). As yet, there is no documentation to verify that the method can be used in practice for a full-scale renovation project.

The method will not necessarily remove all PCBs from the building materials.

5.2.7 Costs

The method generates less waste (3–6 kg/m2) and incurs less cleaning and reconstruction expenses compared to more extensive clean-up methods such as sandblasting, which generates approx. 20 kg of waste per m2.

5.2.8 Extraction in Practice

The best documented approach to extraction involves the application of an organic solvent emulsion (such as toluene, d-limonene, or hexane in water) and possibly a hydrophilic solvent (i.e., an organic solvent miscible in water) such as methanol or ethanol (Quinn et al., 2009). In tests conducted in Denmark, an emulsion of d-limonene in water with ethanol and a small quantity of acetic acid was used.

The method is, in theory, applicable to all types of sources, but not directly to caulked joints (see Section 5.2.2, Types of Treatable Sources). However, residual caulk

left after the caulk has been removed is treatable.

In practice, the surface is often moistened using methylated spirit before applying the extraction agent to increase PCB volatility and to prevent the agent drying out. Furthermore, the extraction agent must be covered with foil and carefully sealed along the edges (e.g., using aluminium tape) to prevent it drying out. If the agent dries out, its effect is lost (Krag & Kastberg, 2012).

Several courses of treatment are usually required. Generally, two treatments are applied to tertiary sources and three to secondary sources. Each treatment must be left for two to three weeks. After each treatment, the area is washed and dried off using water or methylated spirits to remove residues of the extraction agent. As several courses of treatment are required, it may take up to three months to complete the extraction.

When working with extraction agents, suitable PPE must be worn, including respiratory protection and gloves due to the solvents, and possibly a one-piece suit to safeguard against splashing. This method does not generate dust.

The extraction agent is flammable but will not ignite spontaneously. Precautionary measures must be in place, therefore, to prevent fire and explosion hazards. After treatment, the extraction agent must be disposed of as hazardous waste, as it contains PCB. There will be approx. 3–6 kg waste per m2 of treated surface area. Figure 14 shows a photo from a laboratory investigation with extraction paste applied to concrete rods. The concrete rods come from a door rabbet, exposed to secondary contamination by caulk around the door.

Figure 14. Trials with paste for extracting PCBs applied to concrete rods cut from a door rabbet.5.2.9 Remedial Caulk

5.2.9 Remedial Caulk

Remedial caulk is new, interim caulk added to joints to replacing old caulk containing PCBs. They will sorb PCB from adjoining materials for a year or more after which they need replacing. As a rule, remedial caulk should be made using caulk which, in terms of material properties, is as close to the original as possible and is able to absorb movement.

A test should be carried out to assess the caulk’s adhesion and compatibility with contact surfaces. Prior to applying remedial caulk, it is necessary to ascertain whether the surface contains primer and whether this may impair extraction results. A Swedish study showed that primer likely inhibits the migration of PCBs to the caulk (Sundahl et al., 2001).

5.3 Chemical Degradation

Chemical degradation involves reducing PCB content in contaminated materials and thus modifying the source. If PCBs have migrated into the actual material, the method must be combined with extraction.

5.3.1 Mode of Action

PCBs can be treated chemically, degrading the compounds into less harmful substances. This can be done by adding substances which will remove the chlorine atoms on the two phenyl rings (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 1.2 Physico-chemical properties (Andersen, 2015)). This leaves biphenyl, which is less toxic than PCB and will not accumulate in the natural environment.

Bimetallic particles comprising a free metal such as magnesium or iron alloyed with a catalytic agent such as palladium can be added to the extraction agent (Quinn et al., 2009). The metals break down PCBs in the extraction agent by removing the chlorine atoms (DeVor et al., 2009). The end product will usually be biphenyl. Furthermore, laboratory experiments have shown that biphenyl, in some solvents, can be broken down by the bimetallic system (DeVor et al., 2008). In a laboratory experiment, researchers degrade PCBs using magnesium, acid, and solvents (Maloney et al., 2011). This method and the method using the catalytic agent were applied to PCB-contaminated extraction agent in connection with the removal of PCBs from paint on concrete and metal surfaces (Saittan et al., 2015). Both methods had good results.

Several innovative methods exist to degrade PCBs, including biological degradation and degradation using plasma. Biological degradation using micro-organisms have, for example, been used to clean up oil-contaminated soil and can potentially be used for cleaning up PCB-contaminated building materials or in the treatment of PCB-contaminated waste.Plasma is used in air-cleaning systems and has proved capable of degrading PCBs. Plasma can potentially be applied to things other than air. However, the effect of these methods requires documentation. In each separate case, it will be necessary to assess whether there is sufficient reason to select a given method.

Figure 15. It is possible to add bimetallic particles to the extraction agent. Metals will degrade PCB in the extraction agent by removing the chlorine atoms, leaving only biphenyls. Biphenyls are less toxic than PCBs and will not accumulate in the natural environment.

5.3.2 Types of Treatable Sources

Chemical destruction of PCBs is used in to degrade PCBs in marine paints. In the case of PCB migration, chemical degradation is unlikely to be applicable to contaminated surface areas, unless it is combined with extraction (Allen et al., 2011).

5.3.3 Practical Experience

No documented Danish practical experience with chemical degradation of PCBs exists. Generally, chemical degradation of PCBs in building materials is not particularly well-documented (Allen et al., 2011). Laboratory experiments and field studies have been conducted with a view to removing PCBs from paints by chemical degradation by the extraction agent. The findings of these investigations were satisfactory (Saittan et al., 2014 and 2015).

5.3.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

Specific health and safety issues may have to be observed in connection with handling the solvents used to mobilise PCBs. This method is dust-free, so there is no dispersal of PCB-contaminated dust.

5.3.5 Building Usage

When PCBs are broken down as part of the extraction process, it will often be necessary to treat the same building materials several times over with fresh extraction agent,which may take up to three months. This means that building occupants must vacate the treated areas and move elsewhere.

5.3.6 Time Frame and Resilience

The durability of this method has not yet been established, but it is likely comparable to the extraction method.

5.3.7 Costs

Some developmental work remains to render the method cheaper (e.g., by omitting the expensive catalysis metal) (Maloney et al., 2011; Saitten et al., 2015).

5.3.8 Chemical Degradation in Practice

Only limited practical experience exists in Denmark of the so-called activated metal treatment system (AMTS). This is a patented method where the extraction agent is mixed with metals which will degrade PCBs. The technique is identical to extraction (see Section 5.2 Extraction), but no studies involving full-scale renovation have yet been conducted. At the time of writing, the activated extraction agent is too costly compared to the costs of disposing of non-activated extraction agent as hazardous waste (see Section 5.3, Chemical Degradation).

5.4 Bake-Out

Bake-out is also known as ‘thermal stripping’ and consists of reducing PCB content in contaminated materials by heating. This will modify the PCB source. So far, the method has primarily been used to reduce excessive PCB levels in indoor air.

Laboratory experiments have been conducted with bake-out of PCB-contaminated mineral CDW (Hougaard & Mortensen, 2014). Investigations indicate that it is possible to conduct thermal stripping of crushed waste containing secondary and tertiary contaminated materials through bake-out and that the method is suited for large-scale testing. If there are primary sources with a high PCB content among the materials intended for bake-out, the method will not work well. This is because the primary sources will be heated too. This could contaminate materials and prevent optimal clean-up. Furthermore, they may prolong treatment, thereby increasing energy consumption.

5.4.1 Mode of Action

Bake-out is a remediation method that exploits the fact that the emission of PCBs from building materials increases with increasing temperature.

Figure 16. By heating the materials, more PCBs will off-gas than under normal temperatures.

As shown in Figure 17, there is a strong correlation between temperature and the vapour pressure of the separate PCB congeners (Paasivirta & Sinkkonen, 2009). When the temperature rises from 20 to 40 °C, the vapour pressure will increase by a factor of 6–9. The less volatile the congener, the greater the relative increase. At a rise in temperature of 20 to 50 °C, vapour pressure will increase by a factor of 14–23. Moreover, certain investigations into the off-gassing from caulk indicate that a correlation exists between the emission factors and vapour pressure of the separate congeners, meaning that there is a direct correlation between source emission and temperature (Guo et al., 2011).

Figure 17. Dependence of vapour pressure of the seven indicator congeners with the temperature (Paasivirta & Sinkkonen, 2009).By heating the materials, the quantity of gaseous PCB will increase. This increases PCB mobility and thus the rate of off-gassing. During the heating process, quantities of PCB are removed which would take years to off-gas under normal conditions.

A thorough mapping of the PCB contamination is necessary, among other things to avoid baking out primary sources. The potential of the method is conditional on:

- the quantity of PCB which can be removed from the specific area prior to the heating process

- the quantity of PCB left in the remaining material and structures

- how deeply the PCB has migrated into the remaining materials and structures

- how high a temperature the remaining materials and structures can tolerate

- whether bake-out can mitigate excessive PCB concentrations in the indoor air.

Furthermore, the air must be exchanged or cleaned so that off-gassed PCB is removed continuously. PCB emissions from walls are insignificant without cleaning the air during bake-out. Air cleaning or a corresponding air exchange using clean air is thus a precondition for a bake-out to work optimally (Lundsgaard, 2011).

Laboratory experiments can be conducted to determine the off-gassing potential from the individual materials and to verify how much and for how long the materials should be heated. The laboratory experiments can also be used to determine the need for air cleaning during the heating process.

5.4.2 Types of Treatable Sources

Both secondary and tertiary sources can be baked out if the material can tolerate heating. The method is unsuited to primary sources due to their often very high PCB-concentrations. Primary sources should not be subjected to heating, as their off-gassing potential can be so great as to contaminate other materials.

Secondary sources such as concrete adjacent to PCB-containing caulk can be treated by heating it locally (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB bake-out).

There is insufficient documentation to suggest that the method will work for all material types and for all types of secondary and tertiary sources.

5.4.3 Practical Experience

There are several examples of cases in Denmark where the bake-out method has been used (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB Bake-Out).

Heating Locally or Heating Entire Rooms

In two studies, entire rooms were heated and in one, a limited area of secondary contaminated concrete was heated. In all three studies, PCB concentrations in the indoor air had been measured before and after treatment. The measurements indicated that airborne PCB concentrations were reduced by a factor of 1.5–3.3. This indicates that bake-out can be used locally for secondary sources and in entire rooms for tertiary sources.

Two classrooms in a school were part of the study investigating local heating of secondary contaminated concrete. The primary sources were removed in both rooms, but in one room extra effort was expended to minimise spreading and the floor finish and paint on the walls were removed. The reduction of PCB concentrations in the indoor air was relatively higher in this room compared to the other room where only primary sources had been removed.

Length of Heating Period

A study carried out on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate found one brief heating period of five days to be insufficient. The quantity of PCB which can potentially be volatilised by heating was not exhausted after five days of heating. It is possible to remove twice the quantity of PCB by heating for 10 days (Lundsgaard, 2011). The air must be cleaned during heating.

As part of the remediation of the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate, wall surfaces were heated to min. 50° C for 10 days while the air was cleaned by means of recirculating it through carbon filters. Air temperature was typically in the range of 55–70° C. The bake-out was implemented after first having removed primary, secondary, and tertiary sources (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB bake-out and Appendix C. Remediation of PCBs in the Flats on the Farum Midtpunkt Housing Estate).

Combined Bake-Out and Encapsulation

To mitigate excessive exposure levels of PCBs in indoor air in a school, a combined solution was chosen where the most contaminated materials were removed from the building followed by a bake-out and encapsulation of selected surface areas (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB Bake-Out).

5.4.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

The bake-out method is advantageous because the method is dust-free. Recirculated air must be cleaned, and negative pressure must be established in the treated rooms. This contains the off-gassing within the rooms.

If the primary sources are not removed prior to heating, they may emit considerable quantities of PCB to the air and this might considerably elevate PCB levels, perhaps more than can be removed through air cleaning. During the cooling-down period, PCBs may redeposit on all surface areas and later be emitted to the air. A thorough mapping of PCBs prior to the heating process will therefore be necessary.All materials unable to tolerate heating must be removed in advance. Especially flammable and explosive materials. There is also a risk that the remaining building materials may be damaged by heating, as they might expand or dry out.

Visiting the site (e.g., for the purpose of performing control measurements) must be done with due regard to safety during heating.

5.4.5 Building Usage

At a minimum, the building must be vacated for a few months. Prior to the heating process, it will be necessary to go through the building and remove heat-sensitive materials and primary sources. Following this, air cleaners and heating equipment must be installed. It is likely that it will be necessary to repeat the heating process several times over a period of some weeks.

5.4.6 Time Frame and Resilience

The long-term effect of bake-out is, as yet, not well-documented. The long-term effect has only been studied in a single case. Thus far, there are positive results relative to PCB concentrations (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB Bake-Out).

Both before and after heat treatment, PCB concentrations in secondary and tertiary sources should be determined and PCB levels in the air measured. Assessing the long-term effects will probably chiefly apply to the secondary sources, which are often subject to contamination at a greater depth than tertiary sources. In theory, residual PCBs in the material can migrate back into the baked-out material and hence emit to the indoor air.

Treated materials could still potentially contain PCBs.

5.4.7 Costs

There are costs associated with a very detailed mapping of the building to ensure that all PCB sources and furnishings unable to tolerate heat are identified and removed prior to the heating process. Experiments carried out on selected materials before implementing the actual bake-out will also incur costs. There will be expenses associated with purchasing or renting equipment and operational costs for electricity and servicing the equipment for the duration of the abatement intervention. There may be special power supply requirements for the heating and ventilation needed to form negative pressure to prevent emitting high concentrations of PCBs to the indoor air.

5.4.8 Bake-Out in Practice

No precise guidelines for baking out PCBs exist. In practice, however, the bake-out method has been carried out in Denmark using different techniques. Experiences from four cases are gathered in Appendix A, Practical Experience with PCB Bake-Out.

Before implementing remediation at Gadstrup School near Roskilde, studies were carried out into heating and the emission of PCBs from materials from the school (see Appendix A. Practical Experience of PCB Bake-Out). Via systematic laboratory tests of a variety of different materials from the school, studies were made to ascertain whether the bake-out would have the desired effect and for how long, or how many times, the treatment would have to be repeated before the quantity of PCB that could be volatilised had been removed.

Figure 18 shows a fan heater and air cleaner used in a PCB bake-out.

Figure 18. Fan heater and air cleaner used in a PCB bake-out.

5.5 Encapsulation

Encapsulation is a method used to control exposure when discovering excessive PCB levels in indoor air. In certain contexts, the term ’sealing’ is used to describe encapsulation. The method is temporary because the PCB source is not removed and must be addressed at a later point in time. In terms of encapsulation, a distinction should be made between temporary abatement and a more permanent solution. However, this may also be temporary, as the PCBs remain and must be dealt with later.

5.5.1 Mode of Action

Encapsulation involves the enclosure of PCB-contaminated materials, so that the off-gassing of PCBs to indoor air is prevented or abated. This also prevents direct dermal exposure. Encapsulation can either be implemented using a membrane or by surface treatment.

When a primary source is encapsulated, PCB emissions into indoor air will often be reduced, but the effect on PCB concentrations in indoor air will depend, for example, on the number of secondary and tertiary PCB sources identified in the room or building. Secondary and tertiary sources may start emitting PCBs to the indoor air when concentrations drop (see Section 1.1, Spreading of PCBs).

Figure 19. Encapsulation will prevent or reduce PCB off-gassing to indoor air.

Figure 20. Primary sources can be encapsulated, but the effect will depend, for example, on the number of secondary and tertiary PCB sources left.

5.5.2 Types of Treatable Sources

Encapsulating primary sources is an option when quick implementation of remediation work is called for.

As a semi-permanent solution, encapsulation is primarily used for secondary and tertiary PCB sources. Whether it is manageable to encapsulate more extensive surface areas for example, depends on the method used.

In Denmark, encapsulation has been achieved using aluminium tape, applying silicate-based varnish, and special types of paint. Manufacturers recommend that the products be used primarily for secondary and tertiary sources, but certain products can be applied directly to caulk.In Germany, epoxy and polyurethane-based coatings and encapsulation wallpaper using a polyethylene foil with aluminium or active carbon are used for secondary sources (Bonner, 2011). In a German context, secondary sources include what in Denmark are defined as secondary and tertiary sources (see Section 5.1.3, Practical Experience with Physical Removal).

An attractive solution could be to encapsulate secondary sources that are difficult to cut out, such as concrete from load-bearing masonry columns, lintels, etc.

In Germany, a spatial separation of secondary sources and indoor air is practised. This could be a false wall severing contact between secondary sources and indoor air (Bonner, 2011).

5.5.3 Practical Experience

In Denmark, encapsulation has been used in several PCB-contaminated buildings. The method was used where measurements of PCB concentrations in indoor air were slightly above the lower action value of 300 ng/m3 stipulated by the Danish Health Authority. The method has also been used for building parts which cannot be removed for structural reasons.

Encapsulation of Caulked Joints Using Silicate Coating

In most cases, silicate-based varnish has been used for encapsulation without increasing the ventilation rate. There is data from four cases where PCB-containing caulk (primary sources) was encapsulated using silicate coating as the only abatement intervention (Haven & Langeland, 2016).

In one of these cases, a very limited reduction in PCB levels in indoor air was evident fifteen months after the encapsulation. Maximum pre-encapsulation concentrations totalled 464 ng/m3 while post-encapsulation figures totalled 380 ng/m3.

In two cases, respectively 25 % and 46 % reduction of PCB exposure levels in the indoor air were seen just over four years after encapsulation, but this proved inadequate reach the action value of 300 ng/m3 stipulated by the Danish Health Authority.

In the fourth case, a post-encapsulation reduction of 44 % was achieved fifteen months after the intervention. Accordingly, a certain effect can be gained by encapsulating primary PCB sources.

Encapsulation Using Aluminium Tape

There are several documented cases in which encapsulation using aluminium tape was able to reduce indoor-air PCB exposure levels, but the effect was limited and levels below the recommended lower action value of 300 ng/m3 were not achieved (Haven & Langeland, 2011).

Encapsulating PCB-containing caulk with aluminium tape held in place by strips of wood was performed as an acute temporary abatement intervention in the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate. Thus, it was possible to avoid dermal exposure to the PCB-containing caulk. The encapsulation lowered indoor-air PCB exposure levels, but not sufficiently to achieve a satisfactorily healthy environment. Subsequent studies using increased rates of air exchange in two rooms with encapsulated PCB-containing caulk found that tertiary sources (i.e., the contaminated surfaces) emitted PCBs to the indoor air following encapsulation (Lyng et al., 2015) (see Section 1.1, Spreading of PCBs).

Encapsulation and Cleaning

Experience from Germany with a temporary sealing of caulk combined with intensive cleaning in a school showed a mean reduction of indoor-air PCB concentrations of 68 % (Bent et al., 1994).

Encapsulation Using Wallpaper

A German pilot study found that good results were achieved by removing primary sources and encapsulating walls and ceilings using wallpaper containing active carbon, but due to the risk of fire, a full-scale version of the method was not used (Haven & Langeland, 2011). According to Hans Ole Andersen, ZenZors A/S (email, 23/03/2015), this type of wallpaper has a class B fire rating. In a case from the USA, polyethylene foil was applied to the ceiling without any effect, presumably due to the small contribution made by the ceiling source to the total load (Haven & Langeland, 2011).

Laboratory experiments with encapsulation using two kinds of wallpaper were conducted using PERMASORB™ Adsorber Wallpaper and the Surface Emissions Trap (cTrap). Using PERMASORB™ for PCB encapsulation had previously been tested by the manufacturer and indicated a 90 % reduction of indoor-air PCB concentrations. Encapsulating PCB using cTrap has not previously been tested, but it is documented that the product can reduce off-gassing of selected VOCs by 98 % and block particle-bound emissions as well as mycotoxins. Results indicated that the encapsulation could reduce indoor-air PCB concentrations. The reduction was comparable to source removal. However, the potential of extracting PCBs from contaminated materials remains unclear for both types of wallpaper studied (Kolarik et al., 2016).

Encapsulation Using a ‘False Wall’

In a case from the USA, an interior wall was erected to encapsulate PCB supplemented by other abatement interventions. The overall result was positive (Haven & Langeland, 2011).

Encapsulation Using Coatings

In the USA, laboratory experiments have been conducted on coatings, including epoxy, acrylic, polyurethane, polyurea, alkyd, and latex. All the products are available on the US market. Silicate-based coatings were not tested.Results indicate that the most resilient of the coatings tested is epoxy without solvents. However, epoxy is not completely impermeable to PCB migration. Acrylic and latex are the least effective of the materials tested while polyurethane lies somewhere in the middle.

The following factors contribute to the strength of source the material can encapsulate (Guo et al., 2012b):

- Remediation target

- Ability of source to retain PCBs

- Ability of encapsulant to transport PCBs

- Encapsulation thickness

Hence, encapsulation may perform differently relative to the properties of the source material. If the target is a reduction of PCB content in indoor air, consideration should be given to the surface area of the PCB source, other sources, as well as the ventilation system (Guo et al., 2012b).

5.5.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

The application of certain surface treatments requires that special health and safety measures are observed. Liquid products are painted, sprayed, or smeared on while membranes and tapes are bonded (Haven & Langeland, 2016).

Where PCB-containing caulk is required to absorb movement, the resistance of the encapsulation to movement must be documented for the expected remediation lifespan. An assessment must be made in each case as to whether the selected encapsulation method is compatible with the structure in terms of moisture (see Section 5.5.8, Encapsulation in Practice).

Regardless of the selected method of encapsulation, the renovation should be followed up by measurements of indoor-air concentrations over an extended period, preferably a year or more, to document that PCB concentrations remain satisfactory. This procedure is recommended in Germany (Bonner, 2011).

Encapsulation solutions should be documented in detail and documentation be filed with the remaining building-related documentation. Service staff must be acquainted with the solutions and the documentation and should be informed in detail about the significance of the renovation solution for future operations and maintenance of the property.

In the event of a sale or changes in service responsibilities, the owner must ensure that the new owner or service manager is fully informed about the PCB situation in the building. It is necessary to ensure that PCB membranes are not damaged during maintenance work, extensions, or renovations (see Section 2.8.1, After Remediation).

5.5.5 Building Usage

If the encapsulation is performed without removing the caulk, the building can continue to operate, as the encapsulation can be established relatively quickly. Thus, building occupants will only be slightly inconvenienced.For the building owner, this means that occupants will not usually need to be rehoused. If large-scale membranes or surface treatments are applied, the rooms must be vacated, and alternative accommodation found for the occupants. This also applies to the removal of caulk.

5.5.6 Time Frame and Resilience

After encapsulation, there will still be PCBs in the building. It will be necessary, once again, to assess the PCB problem in case of functional change, demolition, or renovation of the building.

In two cases, PCB levels were measured in indoor air after periods of 4 and almost 2 years, after encapsulation of primary sources. In both cases, the encapsulation reduced indoor-air PCB concentrations, but not to levels below the limit of 300 ng/m3 recommended by the Danish Health Authority (Haven & Langeland, 2016). Apart from this, no experience of the long-term effect of this method or the physical resilience of the encapsulation relative to the behaviour of occupants and movement in the structure has been traced in Denmark.

Building owners should be aware of the need for documentation and control measures, particularly when selling their property.

5.5.7 Costs

Compared with many other remediation methods, most encapsulation methods can be planned and implemented much faster and are less costly than methods involving PCB removal. Information on cost is available from two cases involving schools where temporary encapsulation of primary sources were the only abatement interventions performed (Haven & Langeland, 2016).

5.5.8 Encapsulation in Practice

In theory, encapsulation can be used for both primary, secondary, and tertiary sources in a PCB-contaminated building.

The following encapsulant properties should be considered when encapsulating concrete:

- Elasticity or rigidity

- Layer thickness

- Hardness

- Drying or setting time

- Compatibility with existing surfaces

Encapsulation of floor finishes should consist of two differently coloured coatings, so that it becomes evident when a new surface treatment is required because of wear and tear (Mitchell & Scadden, 2001).

The selected sealant must be able to withstand the stress loads to which it will be exposed when the premises are in use.

An assessment must be made in each case as to whether the selected encapsulation method is compatible with the structure in terms of moisture.If there is a risk of moisture in the structure, the encapsulation must be sufficiently vapour-permeable to prevent moisture accumulating in the structure. Rising soil dampness might accumulate in an encapsulated basement wall, for example (Brandt, 2013). Documentation of the moisture diffusion capacity of encapsulants should be considered when assessing the suitability of a particular encapsulation method.

Two types of encapsulation exist: Covering the source with aluminium tape or surface treatment (for example, using a clear specialty varnish).

Encapsulating Using Aluminium Tape

Prior to encapsulating using aluminium tape, joints may be refilled using remedial caulk. This can be done by removing the original caulk, replacing it with new caulk, which will then remediate the area (see Section 5.2.9, Remedial Caulk).

Prior to fixing the adhesive tape, the surfaces adjacent to the joint must be cleaned for the tape to bond properly. The tape must be placed firmly against the substrate without air pockets forming that might connect with the surrounding air. The tape should cover the joint completely.

If there is a risk of physical impact from building occupants, the taped cover should be protected in its entire length by strips of wood or purpose-cut panels. The strips must be firmly fixed to the substrate and completely cover the tape. The tape must not be damaged or ruptured (for example by screws when fixing the strips).

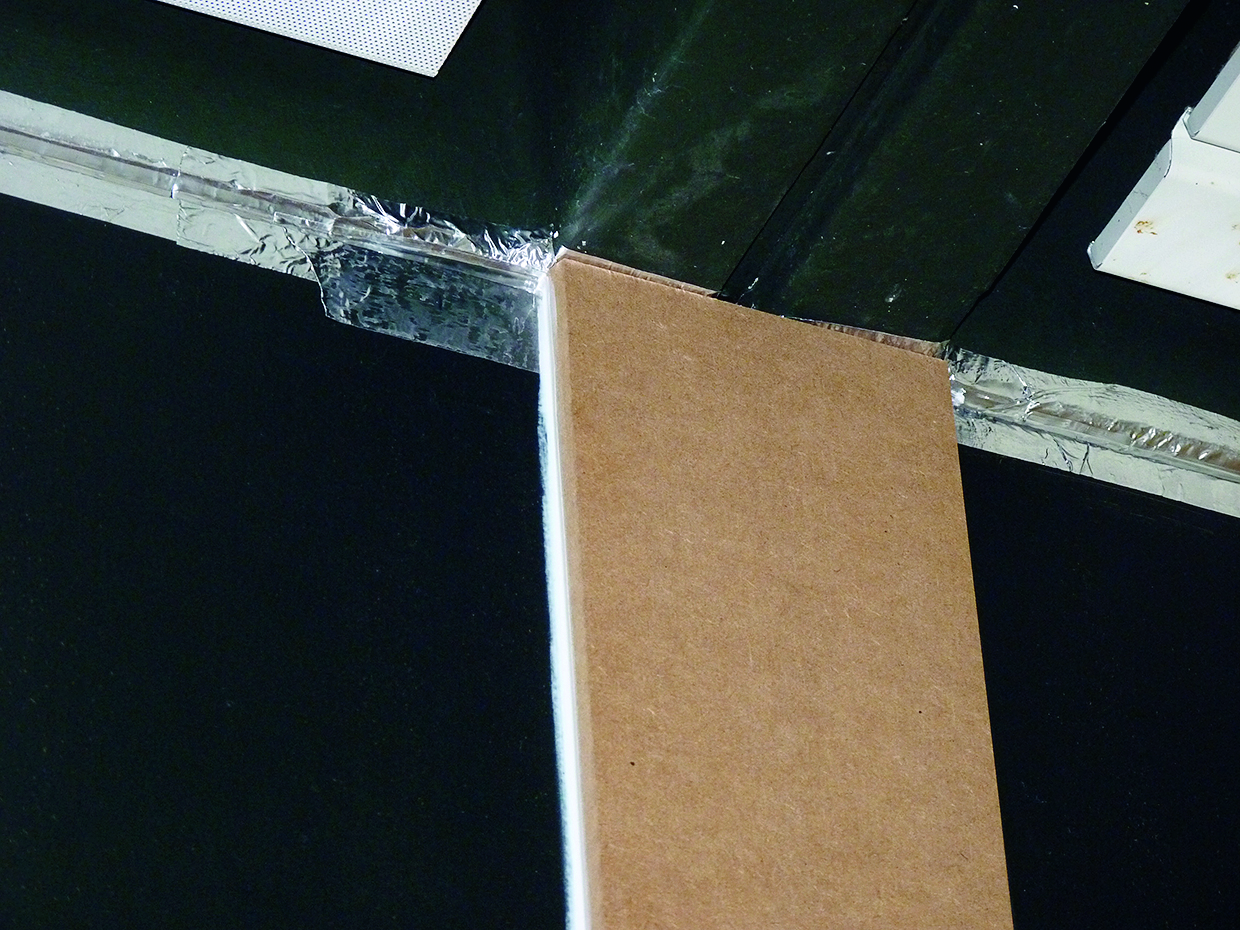

Figure 21 shows an example of an encapsulated area. The wall-to-ceiling joint is covered by aluminium tape while the joint between two wall elements is covered by aluminium tape protected by a wooden panel.

Figure 21. Caulk encapsulated by aluminium tape; on the wall part covered by a wooden panel.

Encapsulation Using Varnish or Surface Treatment

If one decides to remove caulk, it is important to remove as much caulk and backer rod as possible. Subsequently, the surface areas around the joint should be cleaned and the varnish should be applied to the contact surfaces of the new caulk. The manufacturer’s guidelines should be followed or a company experienced in this process should be contracted to apply the varnish. The varnish is often applied in several layers and when dry new caulk is applied on a new backer rod.

If you decide not to remove the caulk, the varnish should be applied over the caulk, making sure to cover the area from the joint and min. 100 mm either side.

Several products are available on the market (e.g., a dual-component epoxy-based product and a Danish silicate-based product). Manufacturers state that their products are primarily suited to secondary and tertiary contaminated building parts such as concrete and painted walls.

When encapsulating extensive surface areas such as walls, make sure that the surface is compatible with the chosen encapsulant.

Follow manufacturer’s guidelines. There may be specific requirements for the application thickness of layers and such requirements must be complied with as the layer thickness may be vital for the effectiveness of the encapsulation.

5.6 Ventilation

Ventilation is a method used to control exposure in case of excessive levels of PCB in the indoor air. Ventilation is only capable of removing insignificant quantities of PCB from the building, but it can help maintain PCB concentrations in indoor air at acceptable levels. Therefore, ventilation is exclusively regarded to mitigate exposure.

Usually, the method is used as an initial temporary abatement intervention. Ventilation for abatement interventions and handling materials containing PCBs is described in Sections 5.4, Bake-Out and 6, Protecting People and the Environment.

5.6.1 Mode of Action

Increasing the rate of air exchange will impact PCB concentrations in indoor air almost immediately and the method is recommended, therefore, as an immediate abatement intervention when excessive concentrations of PCB in indoor air are confirmed (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 9.3 Temporary abatement interventions (Andersen, 2015)).

The Impact of Sources Relative to the Effect

The effect of an increased air exchange rate on PCB concentrations in indoor air is inconclusive. This might be because PCB concentrations in indoor air may impact the off-gassing of PCBs. However, the various source types are affected differently.Changes in PCB concentrations in indoor air will have a very limited effect on the off-gassing from a primary source with a high concentration of PCBs and a relatively small surface area, such as caulk. This means that, all things being equal, increasing the air exchange rate will dilute the source contribution from this kind of primary source.

The level of PCB concentrations in indoor air may have a direct influence on whether tertiary sources will sorb or emit PCB to the indoor air. This applies specifically to tertiary sources with a relatively small PCB content and large surface areas such as walls, ceilings, and floors. If these source types emit PCB to the indoor air, increasing the air exchange rate will contribute to increased emission rates. This means that increasing the air exchange rate will only dilute the source contribution to a very limited extent because the drop in airborne PCB-concentrations is matched by increased off-gassing from tertiary sources.

Increasing the air exchange rate could therefore have less effect on PCB concentrations than expected. This is true despite having removed or encapsulated the primary sources because the secondary and tertiary sources can be so powerful that they may off-gas PCBs to the indoor air to such an extent that PCB concentrations exceed the recommended low action value.

Mechanical Ventilation

Prior to increasing mechanical ventilation, building conditions and airflows must be analysed and checked to ensure that the ventilation system is correctly adjusted and balanced. The location of PCB sources, recirculation, and pressure issues might be significant for PCB concentrations in indoor air.

Figure 22. Increasing the air exchange rate will impact on PCB concentrations in indoor air almost immediately, but it could also increase emissions from the extensive tertiary contaminated surface areas.

Examples show that increased air exchange rates or pressure changes have increased the PCB content in indoor air. Increasing air velocity over the sources in tandem with increasing the ventilation rate might, in turn, increase emissions. If the ventilation system is contaminated with PCBs, recirculation may contribute to elevated concentrations in the room. External joints and one-stage joints containing PCBs also pose a risk if the ventilation is not balanced because negative-pressure ventilation may mean that air containing PCBs will be drawn into the indoor air through the climate envelope. Conversely, positive-pressure ventilation may lead to moisture being driven into the building structure, potentially causing mould growth.

How Much PCB can be Removed by Ventilation?

Based on data from the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate, calculations were made to assess the extent to which PCBs could be removed by an air exchange rate of 0.5 h-1 in a room with a volume of 17.4 m3. If PCB indoor-air concentrations remained at max. 300 ng/m3, the recommended action value stipulated by the Danish Health Authority, the ventilation system will remove 0.023 g PCB per year. This means that it will take 44 years to remove 1 g of PCBs.

In the calculation example from the flats on the Farum Midtpunkt housing estate, the estimated levels of PCB present in the structures were derived from measurements. The concrete contains approx. 33 g of PCBs derived directly from caulk and approx. 11 g of PCBs in the paint and concrete derived from contaminated indoor air (Kolarik et al., 2012) (see SBi Guidelines 241, Survey and Assessment of Building-Related PCBs, 1.5 Primary, secondary, and tertiary sources (Andersen, 2015)).

5.6.2 Types of Treatable Sources

Ventilation is not directed specifically at one source type, but in certain cases can mitigate PCB exposure levels in indoor air.

5.6.3 Practical Experience

The effect of increased air exchange rates is relative to individual buildings, including ventilation conditions prior to remediation.

Data collected from 28 cases implementing permanent abatement interventions indicated that the post-remediation airborne concentration in 19 of these cases were below 300 ng/m3, the recommended action value stipulated by the Danish Health Authority (Haven & Langeland, 2016). In 9 of the 19 cases, the setting up or upgrading of the ventilation system formed part of the abatement interventions. In only one case, ventilation had been the single permanent solution. In this case, studies found ventilation conditions to be of great significance for the concentration of PCBs in the indoor air.

A review of several additional cases from eight different buildings using mechanical ventilation indicates a certain reduction in PCB concentrations in indoor air in most of the cases when the ventilation was increased, correctly adjusted, and balanced (Lyng et al., 2014). In these cases, the effect had been assessed by turning the mechanical ventilation on and off.

Increasing the air exchange rate does not always result in a corresponding drop in PCB concentrations. These were the findings of field studies in a classroom and two bedrooms with encapsulated internal PCB-containing caulk. The increased air exchange rate was only able to dilute the source contribution to a very limited extent because the drop in airborne PCB concentrations was matched by increased off-gassing from secondary and tertiary sources (Lyng et al., 2015). Therefore, increasing ventilation might have less of an effect on PCB concentrations than expected. The greatest drop in airborne PCB concentrations in rooms with encapsulated sources is expected to occur when the ventilation is increased from a very low level. Increased air velocity over the source may contribute to increased emissions.

5.6.4 Occupational Health and Safety Aspects

Increased ventilation does not pose a safety risk but may lead to building occupants being inconvenienced by draught and noise.

Ongoing documentation of PCB concentrations in indoor air should be conducted to ensure that levels do not exceed recommended action values.

5.6.5 Building Usage

Occupants can use the building normally; however, they may be inconvenienced by draughts and noise.

5.6.6 Time Frame and Resilience

Increased ventilation can be a temporary or permanent abatement intervention. In some cases, ventilation can be sufficient to achieve acceptable PCB concentrations Failing that, ventilation can be combined with additional measures. If ventilation is combined with more permanent remediation solutions, in time these may reduce the need for increased ventilation.

Building owners should be aware of the need for documentation and control measures.

5.6.7 Costs

Increased ventilation means greater day-to-day operational building costs. The costs associated with increased mechanical ventilation will depend on the existing system (see Section 5.6.8, Ventilation in Practice).

5.6.8 Ventilation in Practice